Steven Tang

Senior Investment Consultant, Zenith Investment Partners

Matthew Cho

Investment Consultant, Zenith Investment Partners

Despite most expectations, 2018 proved to be a very disappointing and jarring year for investors. Not only did volatility return in abundance, particularly in the first and last quarters of the year, but almost all asset markets ended the year in negative territory.

The equity market darling for most the year, the US stock market suffered a double-digit decline in the fourth quarter, ending its worst year since 2008. Surprisingly, global and Aussie bonds were the only shining light, outperforming most developed equity markets, an outcome few would have predicted at the start of 2018.

Chart 1: Asset class performance 2018

Given this backdrop, what’s the outlook for 2019 and what could sideswipe markets? The consensus is that the outlook has become more uncertain, with the tail risks to global markets now larger than they were 12 months ago. There are plenty of known risks, that have been well documented in the media, including:

- Brexit;

- Ongoing US-China trade war;

- China slowdown;

- Central Bank policy (US rate rises and quantitative tightening); and

- The large build-up in corporate debt.

However, while the outcomes of these risks aren’t known, it could be argued that markets have somewhat priced in the possible scenarios.

But what about risks that aren’t priced into markets? Former US defence secretary, Donald Rumsfield, famously referred to these as “unknown unknowns”. That is to say, there are risks that few investors have factored in, for example, major Arab conflict. These are what generally sideswipe markets.

Amongst the perceived increasing level of uncertainty, investors are now more than ever seeking guidance as to the course of markets in 2019.

Forecasting – an exercise in futility

Many investors will look to ‘so-called’ experts, who will release their forecasts for markets over the coming year. However, are these forecasts worth the time and effort that investors spend pouring over them?

To help answer this question, let’s reflect on the year just gone.

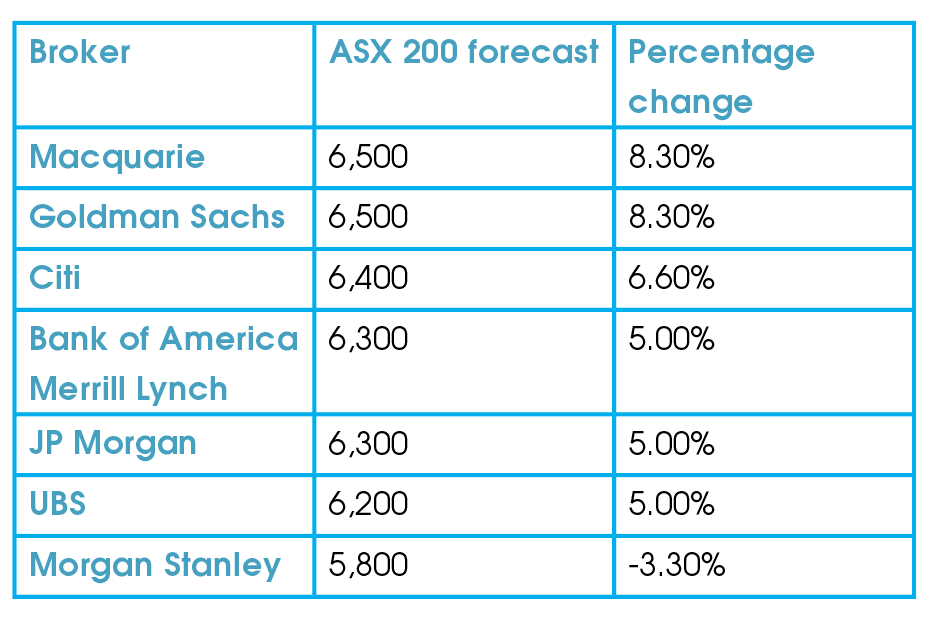

At the beginning of 2018, the median broker forecast for the ASX200 was 6,300, representing a calendar year return of 6.3 per cent. If an investor had taken this on board and invested wholly into the index, they would have generated a realised return of -3.07 per cent.

Commentators were also overly optimistic in the United States. For the S&P 500, the median forecast price at the end of 2018 was 2,950 points, for a 2018 calendar year return of 10.3 per cent. The realised return was -4.38 per cent.

Opinions in Europe were just as erroneous, with strategists expecting a 1.5 per cent annual return for the FTSE 100 at the beginning of the year, but the realised return was -12.5 per cent. For the EuroStoxx 50, the predicted return was 7 per cent and for a realised return of -14.24 per cent.

Moving over to fixed income markets, how do the experts fair in this domain?

Let’s focus on Jerome Powell and his economics team at the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed). Generally revered as omnipotent, how have they fared in terms of where interest rates might go?

Movements in the Fed’s predictions (dot plots) make ripples in investment markets globally. However, the Fed – just like everybody else – has a poor record of forecasting outcomes. In fact, the Fed has been overly optimistic on the trajectory of interest rates for some time.

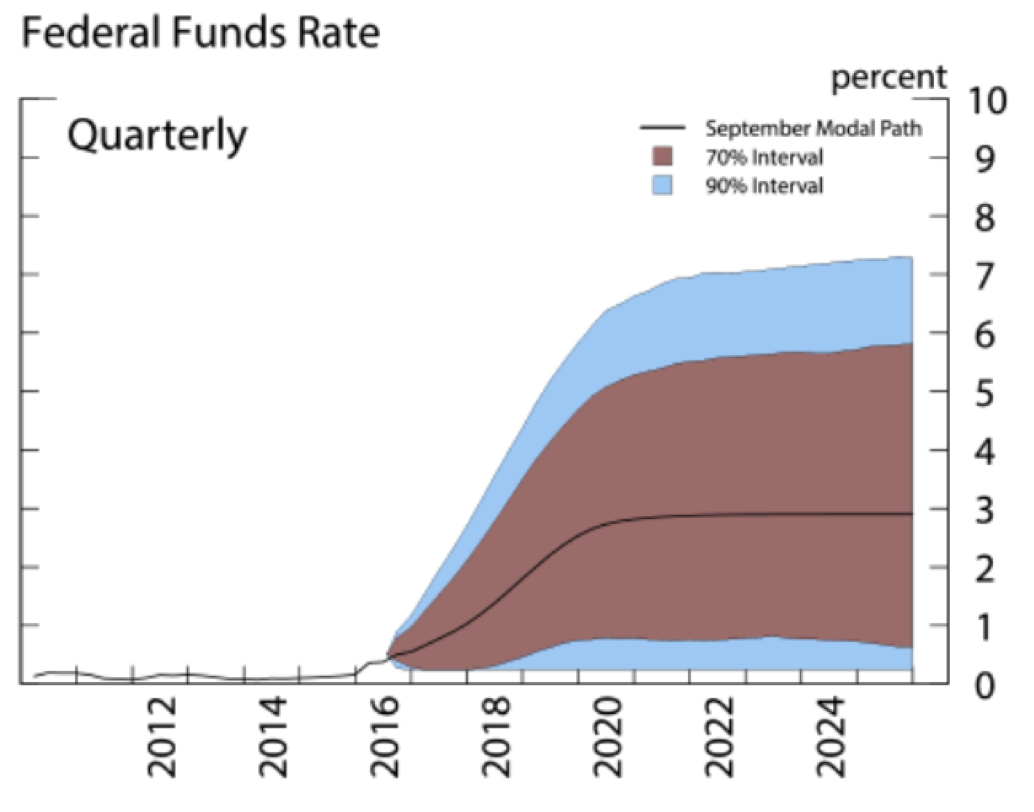

To make matters worse, the Fed itself seems to have little confidence in its forecasts. Chart 2, produced by the Fed, demonstrates with how much confidence the Fed believes it can forecast rates at 70 per cent and 90 per cent intervals.

Chart 2: Federal Funds Rate

Chart 2, produced in 2017, shows how little confidence the Fed has in its own predictions. While the Fed expects the long-term rate to be around 3 per cent, it can only assign a 90 per cent certainty that the Fed Funds rate will lie between approximately 0 per cent and 7 per cent. Given the wide range, investors should take the dot plots with a grain of salt.

What about economists?

Investors often believe that stock markets reflect the economic conditions of their respective countries. They hypothesise that if an economy is growing, output will be increasing and firms should be experiencing increased profitability, with the opposite also true.

Assuming this is true over the shorter-term, it would still be necessary to have accurate forecasts to enable investors to take advantage of this hypothesis. So, how do professional economists fair in their predictions and can their forecasts help us navigate markets?

Unfortunately, the answer is most likely ‘no’ in terms of forecasting skill, as economists have shown limited ability to predict the direction and magnitude of growth. Even all the PhDs at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have shown very little success. Over the past 27 years, the IMF has predicted on average that five economies would be in recession, when in reality the number has been 26.

Furthermore, they tend to have the greatest error when it matters the most. In October 2009, the IMF predicted economic expansion for the U.S. and Japan. However, instead, the U.S. contracted close to 3 per cent and Japan a whopping 5.4 per cent.

However, even if you manage to forecast with near perfect foresight, it’s been shown that the short-term linkage between GDP growth and stock returns is weak. 2018 was a great example; the U.S. economy expanded at a rate of 3.4 per cent at the end of the third quarter and U.S. equities declined -4.38 per cent. A clear disconnect, as the U.S. economy continued to perform well and earnings growth remained robust, however, markets were plagued by macroeconomic and sentiment issues.

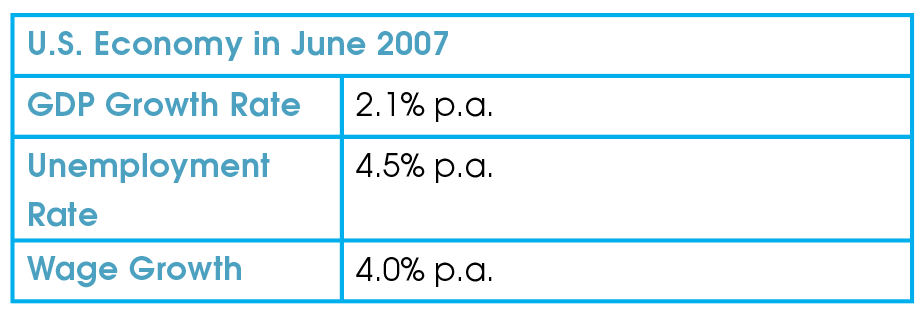

Similarly, in the years leading up to the GFC, economic conditions within the U.S. and globally were favourable. Economic growth was strong, rates of inflation were stable, and unemployment and wage growth were healthy. However, the catalysts that emerged were not apparent from these headline figures, and caught most economists and investors wrong-footed.

Table 2: U.S. economy in June 2007

How to prepare clients for the period ahead

As humans, we love certainty, which is why we gravitate to ‘so-called’ expert forecasts, time and time again; even though we know they will almost certainly be wrong.

In saying this, we’re not questioning the skill of these experts, merely pointing out that predicting the future is almost impossible, because it relies on numerous assumptions and a pre-determined series of events occurring.

More often than not, the unknown unknowns get in the way of the central thesis and take markets on a different path. You only need to think back to the decision by the U.K. to exit the European Union in June 2016 or Trump’s victory in the U.S. elections in November 2016; and the markets’ initial and subsequent reactions to these events to realise this.

More so, one of Warren Buffett’s famous quotes, “In the short-run, markets are a voting machine but in the long-run, they’re a weighing machine”, that is, sentiment drives markets in the short-run and is a fickle beast.

Clients need to accept uncertainty is part of investing, as in life. The only certain return is cash (at least in nominal returns), and that’s not going to give investors the returns they require over the longer-term.

It’s interesting that people always believe there is less certainty at any given time, when in fact, there is never any certainty. No one can tell you what’s going to happen tomorrow, next month or next year. The biggest challenge for clients is the behavioural aspect of investing – for example, not selling low and buying high, having the conviction and fortitude to stay the course.

Investors are often tempted to time markets; they employ tactical asset allocation to go to cash in times of market stress. However, doing so requires exquisite timing, not only on the exit but also on the re-entry (this ignores transaction and tax costs). Missing only a few days in the market can dramatically impact your longer-term returns.

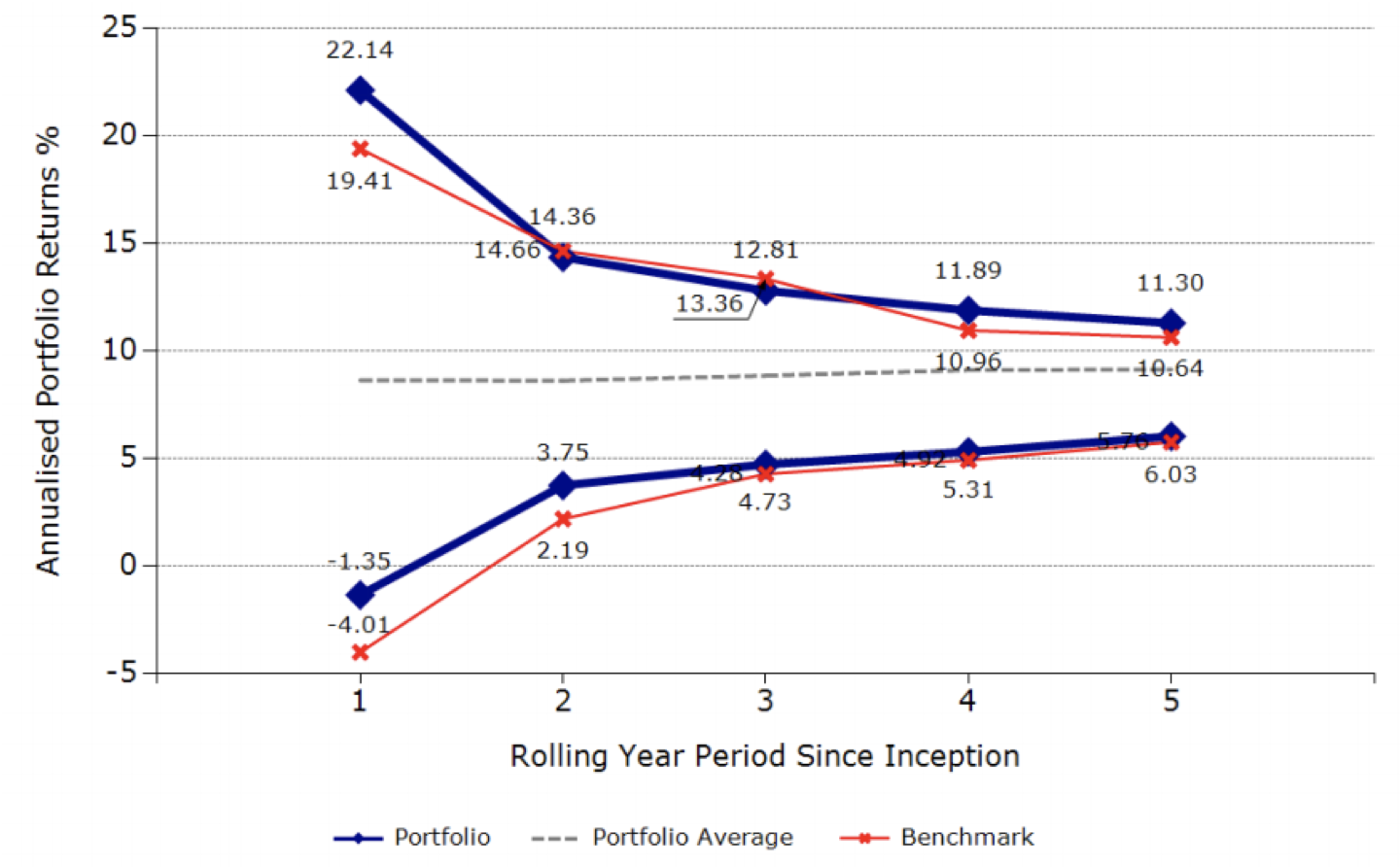

Having an appropriate time horizon is the key to successful investing. While over the short-term, the direction of asset markets isn’t predictable, over the longer-term, the dispersion of returns decreases dramatically. The return funnel in Chart 3 shows the dispersion on rolling annual periods for a balanced fund (60 per cent growth/40 per cent defensive split).

Chart 3: Rolling year

What does this mean for portfolios?

If we accept that there’s no way to predict the direction of markets in the year ahead with much certainty, how should investors position their portfolios?

To borrow a line from Jacob Mitchell (Chief Investment Officer at Antipodes Global Investors), they need to embed “multiple ways of winning” in portfolios; one that is not reliant on a narrow outcome. That is to say, while it’s prudent to remain vigilant to the risks in portfolios, the best defence against market weakness, is to have appropriate diversification.

Diversification can often be a throw away line but if executed properly, this can mean that portfolios are more resilient to lots of different scenarios and outcomes.

Investors should seek to understand how sensitive portfolios are to different economic conditions, which is where quantitative tools (optimisers, stress and scenario testing) can be very insightful. However, such tools have limitations and qualitative judgement should always be exercised.

This means that portfolios should be diversified not only across asset classes but within asset classes and across strategies. However, for this diversification to be an effective strategy, investors should remember that having an appropriate time horizon is key, preferably one that looks beyond 2019.

Steven Tang is Senior Investment Consultant at Zenith Investment Partners and Matthew Cho is Investment Consultant at Zenith Investment Partners.